Friday, October 30, 2009

Sunday, October 25, 2009

Thursday, October 22, 2009

Wednesday, October 21, 2009

Sunday, October 18, 2009

Saturday, October 17, 2009

Sibling Topics (section a)

Lexy saw this a few months back at a show in Philly, she just showed it to me on vimeo. I felt you all needed to see it. Its fucking great.

Wednesday, October 14, 2009

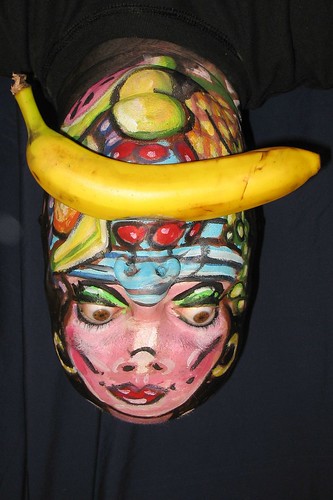

Artist Profile: James Kuhn

" If you want to make art of any kind, you must be creative. If you want to go where no man has gone before, you must be radically inventive! Push, push, push! into your unknown. Stretch the borders of your comfort zone and allow yourself to be uncomfortable and vulnerable. In art, fear is your friend - It is your geiger counter. If you are not a little bit afraid, then you might as well stop wasting paper and paint! Fearlessness in the face of fear separates the men from the boys, the hobbyist'ss from the true innovators. True art is original and thought provoking, it can bring you to tears or make you laugh, and it can disturb you, but what disturbed you yesterday quickly becomes commonplace and old hat. You must continually move forward into the new. " - James Kuhn

" If you want to make art of any kind, you must be creative. If you want to go where no man has gone before, you must be radically inventive! Push, push, push! into your unknown. Stretch the borders of your comfort zone and allow yourself to be uncomfortable and vulnerable. In art, fear is your friend - It is your geiger counter. If you are not a little bit afraid, then you might as well stop wasting paper and paint! Fearlessness in the face of fear separates the men from the boys, the hobbyist'ss from the true innovators. True art is original and thought provoking, it can bring you to tears or make you laugh, and it can disturb you, but what disturbed you yesterday quickly becomes commonplace and old hat. You must continually move forward into the new. " - James KuhnOther Works:

and an overview of his portfolio...

Tuesday, October 13, 2009

Monday, October 12, 2009

Sunday, October 11, 2009

The Summit of All Fears... Crunchholdoh!

Crunchholdoh.net (also the name of the album)

Saturday, October 10, 2009

Thursday, October 8, 2009

The Rebellion of Scene

Commercial Breakers from Douglas Haddow on Vimeo.

So I thought I'd post this as a sort of follow up to my last post. I think adbusters is pretty good, I mean I'm not 100% convinced, but for now I think I'm really digging what their trying to do as a creative voice. Are they completely aware of their actions? I'm not sure, but it's definitely a step in the right direction, and we as a culture desperately need more voices like theirs. I think they as a collective have made that all important distinction in their minds of who "the new federalists" in our culture are. They at least seem on the right track since this ad was supposedly rejected by both FOX and MTV. I say well done, and I'm interested in seeing where their headed. With that being said, I'm not sure that they're smart enough to create a format for which a true cultural subversion could take place. I'd like to be wrong, but I'm just not sure it's in there, what do you think?

Wednesday, October 7, 2009

The Electronic Hive: Ebrace It

Ok, so I found this article republished in the current issue of adbusters. On first reading I of course assumed this was a current, recently written and published piece, but upon reaching the end of the essay I was pretty floored to find that this was written only a month after Kurt Cobain blew his brains out. It's this kind of complete understanding of the present tense that I really envy. Are we past this yet? Have we even gotten there? If we have, where is there to go from here? I'm sure this sort of anxiety has been felt before, but in this Gutenberg-like shift in how we receive information it's easy to feel completely overwhelmed with the enormity of it all...

If twentieth-century science can be said to have a single icon, it is the Atom.

As depicted in the popular mind, the symbol of the Atom is stark: a black dot encircled by the hairline orbits of several smaller dots. The Atom whirls alone, the epitome of singleness. It is the metaphor for individuality. At its center is the animus, the It, the life force, holding all to their appropriate whirling station. The Atom stands for power and knowledge and certainty. It conveys the naked power of simplicity.

But the iconic reign of the Atom is now passing. The symbol of science for the next century is the dynamic Net.

The icon of the Net, in contradistinction to the Atom, has no center. It is a bunch of dots connected to other dots, a cobweb of arrows pouring into one another, squirming together like a nest of snakes, the restless image fading at indeterminate edges. The Net is the archetype displayed to represent all circuits, all intelligence, all interdependence, all things economic and social and ecological, all communications, all democracy, all groups, all large systems. This icon is slippery, ensnaring the unwary in its paradox of no beginning, no end, no center.

The Net conveys the logic of both the computer and nature. In nature, the Net finds form in, for example, the beehive. The hive is irredeemably social, unabashedly of many minds, but it decides as a whole when to swarm and where to move. A hive possesses an intelligence that none of its parts does. A single honeybee brain operates with a memory of six days; the hive as a whole operates with a memory of three months, twice as long as the average bee lives. Although many philosophers in the past have suspected that one could abstract the laws of life and apply them to machines, it wasn't until computers and human-made systems became as complex as living things -- as intricately composed as a beehive -- that it was possible to prove this. Just as a beehive functions as if it were a single sentient organism, so does an electronic hive, made up of millions of buzzing, dim-witted personal computers, behave like a single organism. Out of networked parts -- whether of insects, neurons, or chips -- come learning, evolution, and life. Out of a planet-wide swarm of silicon calculators comes an emergent self-governing intelligence: the Net.

I live on computer networks. The network of networks -- the Net -- links several million personal computers around the world. No one knows exactly how many millions are connected, or even how many intermediate nodes there are. The Internet Society made an educated guess last year that the Net was made up of 1.7 million host computers and 17 million users. Like the beehive, the Net is controlled by no one; no one is in charge. The Net is, as its users are proud to boast, the largest functioning anarchy in the world. Every day hundreds of millions of messages are passed between its members without the benefit of a central authority. In addition to a vast flow of individual letters, there exists between its wires that disembodied cyberspace where messages interact, a shared space of written public conversations. Every day authors all over the world add millions of words to an uncountable number of overlapping conversations.

They daily build an immense distributed document, one that is under eternal construction, in constant flux, and of fleeting permanence. The users of this media are creating an entirely new writing space, far different from that carved out by a printed book or even a chat around a table. Because of this impermanence, the type of thought encouraged by the Net tends toward the non-dogmatic -- the experimental idea, the quip, the global perspective, the interdisciplinary synthesis, and the uninhibited, often emotional, response. Many participants prefer the quality of writing on the Net to book writing because Net writing is of a conversational, peer-to-peer style, frank and communicative, rather than precise and self-consciously literary. Instead of the rigid canonical thinking cultivated by the book, the Net stimulates another way of thinking: telegraphic, modular, non-linear, malleable, cooperative.

A person on the Internet sees the world in a different light. He or she views the world as decidedly decentralized, every far-flung member a producer as well as a consumer, all parts of it equidistant from all others, no matter how large it gets, and every participant responsible for manufacturing truth out of a noisy cacophony of ideas, opinions, and facts. There is no central meaning, no official canon, no manufactured consent rippling through the wires from which one can borrow a viewpoint. Instead, every idea has a backer, and every backer has an idea, while contradiction, paradox, irony, and multifaceted truth rise up in a flood.

A recurring vision swirls in the shared mind of the Net, a vision that nearly every member glimpses, if only momentarily: of wiring human and artificial minds into one planetary soul. This incipient techno-spiritualism is all the more remarkable because of how unexpected it has been.

The Net, after all, is nothing more than a bunch of highly engineered pieces of rock braided together with strands of metal or glass. It is routine technology. Computers, which have been in our lives for twenty years, have made our life faster but not that much different. Nobody expected a new culture, a new thrill, or even a new politics to be born when we married calculating circuits with the ordinary telephone; but that's exactly what happened.

There are other machines, such as the automobile and the airconditioner, that have radically reshaped our lives and the landscape of our civilization. The Net (and its future progeny) is another one of those disrupting machines and may yet surpass the scope of all the others together in altering how we live. The Net is an organism/machine whose exact size and boundaries are unknown. All we do know is that new portions and new uses are being added to it at such an accelerating rate that it may be more of an explosion than a thing. So vast is this embryonic Net, and so fast is it developing into something else, that no single human can fathom it deeply enough to claim expertise on the whole.

The tiny bees in a hive are more or less unaware of their colony, but their collective hive mind transcends their small bee minds. As we wire ourselves up into a hivish network, many things will emerge that we, as mere neurons in the network, don't expect, don't understand, can't control, or don't even perceive. That's the price for any emergent hive mind.

At the same time the very shape of this network space shapes us. It is no coincidence that the post-modernists arose as the networks formed. In the last half-century a uniform mass market has collapsed into a network of small niches -- the result of the information tide. An aggregation of fragments is the only kind of whole we now have. The fragmentation of business markets, of social mores, of spiritual beliefs, of ethnicity, and of truth itself into tinier and tinier shards is the hallmark of this era. Our society is a working pandemonium of fragments -- much like the Internet itself.

People in a highly connected yet deeply fragmented society can no longer rely on a central canon for guidance. They are forced into the modern existential blackness of creating their own cultures, beliefs, markets, and identities from a sticky mess of interdependent pieces. The industrial icon of a grand central or a hidden "I am" becomes hollow. Distributed, headless, emergent wholeness becomes the social ideal.

The critics of early computers capitalized on a common fear: that a Big Brother brain would watch over us and control us. What we know now of our own brains is that they too are only networks of mini-minds, a society of dumber minds linked together, and that when we peer into them deeply we find that there is no "I" in charge. Not only does a central-command economy not work; a central-command brain won't either.

In its stead, we can make a nation of personal computers, a country of decentralized nodes of governance and thought. Almost every type of large-scale governance we can find, from the body of a giraffe, to the energy-regulation in a tidal marsh, to the temperature regulation of a beehive, to the flow of traffic on the Internet, resolves into a swarmy distributed net of autonomous units and heterogeneous parts.

No one has been more wrong about computerization than George Orwell in 1984. So far, nearly everything about the actual possibility-space that computers have created indicates they are not the beginning of authority but its end.

In the process of connecting everything to everything, computers elevate the power of the small player. They make room for the different, and they reward small innovations. Instead of enforcing uniformity, they promote heterogeneity and autonomy. Instead of sucking the soul from human bodies, turning computer-users into an army of dull clones, networked computers -- by reflecting the networked nature of our own brains and bodies -- encourage the humanism of their users. Because they have taken on the flexibility, adaptability, and self-connecting governance of organic systems, we become more human, not less so, when we use them.

Originally published as the second part in The Electronic Hive: Two Views (pdf), with Sven Birkerts, in Harper's Magazine, May 1994, vol. 288, no. 1728, pp. 17(7)Tuesday, October 6, 2009

Monday, October 5, 2009

Sunday, October 4, 2009

Katfight

"Why Battlestar Galactica is not so Frakking Feminist After All"

http://www.slate.com/id/2213006/

"The Men Who Make Battlestar Galactica Feminist" (a reply)

http://io9.com/5165920/the-men-who-make-battlestar-galactica-feminist

Friday, October 2, 2009

Jonathan and Nate's A-List Podcast, Episode 4

"Can't Bear to Care" <---click here

Bill Nye - Sex talk

They Might Be Giants - How the Sun Really Shines

Masato Nakamura - Mushroom Hill Act 1

Animal Collective - Slippi

The Ventures - Perfidia

Sun Araw - Get Low

Carl Sagan, ft. Stephen Hawking - A Glorious Dawn

Om - Cremation Ghat II

The Christian Ramones - Wash Away Sin

Alabama Sacred Harp Singers - Rocky Road

Care Bear - Craft Fair

Iggy Pop - Success

Chicago - I'm a Man

Roky Erikson - Night of the Vampire

The Ronettes - Chapel of Love